Everything is bigger in Texas, including Oath Breakers

Fiascos, usually, happen because of people making bad decisions.

Author’s Note: This is a long post. Like a long drive to somewhere lovely, I think it is worth it. Though to earn your prolonged attention, there is a surprise at the end for the finishers.

Last fall, while I was on unpaid leave from my job as a professor—campaigning, my colleague, also an engineer, sent me a text saying how much they missed me. The floor with all the faculty offices on it was eerily quiet. In pop culture engineers are usually considered introverts and maybe somewhat sedate; I am clearly an exception.

My math-brained colleague and I once got into a fierce debate: are vectors real? (I may have started it) I argued they're just fantastically useful but still imagined from an abstract framework, not something you'll ever unearth from a tomb. (Seriously, good luck finding a ‘unit vector’—that dimensionless, magnitude-of-1 directional arrow—buried with Tutankhamen!) First-year students often puzzle over these "made-up" quantities with magnitude and direction (like velocity!) versus simple magnitudes (like temperature), I remind them: like most math, these conjured rules, from algebra to trigonometry, are incredibly, wonderfully useful for describing reality—but entirely made-up.

I may go a little far in teasing the math people on the floor—but I am not the only one. This comic hangs in our hallway:

After boasting in a Dynamics class that most famous mathematicians only become renowned for physics or astronomical findings, I once found a list of handwritten names on my desk from our beloved mathematician—the result, I later discovered, of students having ratted me out. The list was of 'pure' mathematicians, none of whom I'd ever heard of.

Sometimes, though, serious discussions emerge. One that stands out concerns academia’s approach to assessing engineering students’:

ability to recognize ethical and professional responsibilities in engineering situations and make informed judgments, which must consider the impact of engineering solutions in global, economic, environmental, and societal contexts.—ABET Outcome 4

I argue, I don’t need to administer standardized ethics tests. The results in industry tell me we are failing, or perhaps our efforts are simply snuffed out by corporate interests. You can’t swing a dead cat without hitting an engineering ethics case study: Boeing. Takata (remember the airbags?). Challenger. Vaping. I could go on and on. (Seriously, I had to cut so much here.)

Given that litany of disasters, it's almost ironic to point out this next bit: Each discipline—Civil, Mechanical, Electrical, etc.—has a code of ethics. All of them have some variation, but their preambles unequivocally state that the engineer's highest professional duty is to hold “paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public.” This is the fundamental guiding principle. An oath.

But you wouldn't know that from looking at industry. You might exclaim, “bullshit.” The real reason, I argue on our floor and at happy hour with my colleagues, that we have any product safety is because of Strict Liability: “the manufacturer of an article is liable for any damage or harm that results because of a defect, known or unknown.” Indeed, if not for criminal codes and product liability lawsuits (gun manufacturers, notably, being an exception)—but I'm getting carried away here—product safety as we know it would barely exist.

We live in an era where oaths are perfunctory. Oaths, once solemn vows, have become meaningless, and toothless in contemporary society. To grasp the gravity of this decay, consider the fundamental commitment made by the Secretary of Homeland Security, who is responsible for national security—covering not just immigration enforcement, but also the preparedness for and the responses to terrorism and disaster, makes:

Yet, the devastating consequences of perfunctory oaths are heartbreakingly evident, pervasive in the Trump Administration. Kristi Noem, the sworn Secretary of Homeland Security, delayed the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) response by 72 hours after terrible flooding in Texas, due to one of the administration’s ‘stupid DOGE policies’—a policy, mind you, that required the Secretary’s approval for expenses exceeding $100,000. (Only a mouth-breathing dunderhead would set that limit; if FEMA is required, the costs of mobilizing search and rescue, recovery, and assistance will blow past $100,000 in a heartbeat.) This policy directly impacted the tragic flooding in central Texas, where over 120 people have died.

Unbelievably, in the United States of America in 2025, two thirds of survivors from the Texas flooding were unable to connect with Noem’s FEMA:

“Two days after catastrophic floods roared through Central Texas, the Federal Emergency Management Agency did not answer nearly two-thirds of calls to its disaster assistance line…The lack of responsiveness happened because the agency had fired hundreds of contractors at call centers.”—New York Times, July, 11th, 2025

But this erosion of commitment isn't confined to federal offices. The problem extends to the local level. Consider, too, the situation in Kerr County, Texas. Amidst the devastating flooding, the County Judge and commissioners—the very individuals tasked with managing the budget, including tax and revenue for the county, as outlined by the Kerr County Structure —had also taken a solemn oath of office:

And yet, ProPublica reported that some local officials did not sound the alarm and try to remove their constituents from the storm’s path even though the National Weather Service had sent urgent alerts about potentially life-threatening danger hours in advance of the flash floods. ProPublica quoted, Accuweather’s chief meteorologist, Jonathan Porter, who simply stated:

“There was plenty of time to evacuate people to higher ground,” Porter said. “The question is, Why did that not happen?”

Well, reporting by the Texas Tribune revealed that the county commission was aware of the flash flooding risk for more than a decade, but did not want to end their political careers, spend the political capital on the publicly unpopular decision to raise taxes for an emergency flood warning system.

Unfortunately, Kerr County also fell victim to the challenges of grant writing—the agency that administers federal disaster funds in Texas-rejected a request for nearly 3/4 of million dollars to install 20 flood gauges, 10 high water detectors and sirens—because they did not have an hazard mitigation plan.

Compounding this, a pervasive mindset, cultivated by toxic political rhetoric from the right over the last forty years, led Kerr County residents to reject a proposal to use American Rescue Plan money to install the system—many advocating for the outright refusal of the funds:

“I’m here to ask this court today to send this money back to the Biden administration, which I consider to be the most criminal treasonous communist government ever to hold the White House,” one resident told commissioners in April 2022, fearing strings were attached to the money.

“We don't want to be bought by the federal government, thank you very much,” another resident told commissioners. “We'd like the federal government to stay out of Kerr County and their money.” -Texas Tribune

Such sentiments, with their defiant disregard for collective well-being, bring to mind a certain privileged, petulant character from fiction: Willy Wonka's Veruca Salt. Their cry of "I don't want this federal money!" — Isn't just self-centered or short-sighted; it's an ideological, surly insistence on perceived independence that leads directly to rejecting vital assistance and dismissing clear risks, even when collective safety is at stake.

When such self-serving ideologies prevail, the cost is measured in lives.

The deadly and catastrophic fallout from the Texas flooding was not just an act of nature but a direct consequence of a societal failure to uphold critical oaths—both by those in public office and in engineering professions—where short-term interests trump public safety.

Risk—it's a tricky concept, at once deeply technical and profoundly psychological. Consider, for instance, how many people are afraid of flying, yet willingly get into a car every day. This paradox speaks volumes about our perception, our ability—or inability—to predict the future, and our inherent judgment calls.

Technically, risk is defined as ‘an estimate of the probability of a hazards-related incident or exposure occurring and the severity of harm or damage that could result.’ Safety, conversely, is ‘the state for which the risks are judged to be acceptable.’ In engineering, determining whether a thing, an activity, or an environment is safe requires making a deliberate decision.

But here’s where the human element complicates matters: everyone has a different risk tolerance. Some people are risk-averse, some are risk-neutral, and some are risk-prone. Our perception of risk is often contaminated by various biases, leading us to be "risk blind" or to underestimate actual dangers when cult leaders other objectives drive our decisions. For example, availability bias means if you haven't seen an incident before—like measles or polio in recent generations—you might underestimate its actual risk and not get your kid vaccinated. In general, people tend to underestimate the risk of high-probability, high-impact events (like dying in a car crash) while overestimating the risk of low-probability, high-impact events (like being in an airplane crash). It is the equivalent of looking for evidence of tampering on a bottle of acetaminophen but taking more than the recommended amount for longer than the recommended time.

Ultimately, understanding risk isn't just about crunching numbers; it's also about confronting the sociological and psychological factors that shape our judgment. It requires deep analysis, far beyond simple calculation.

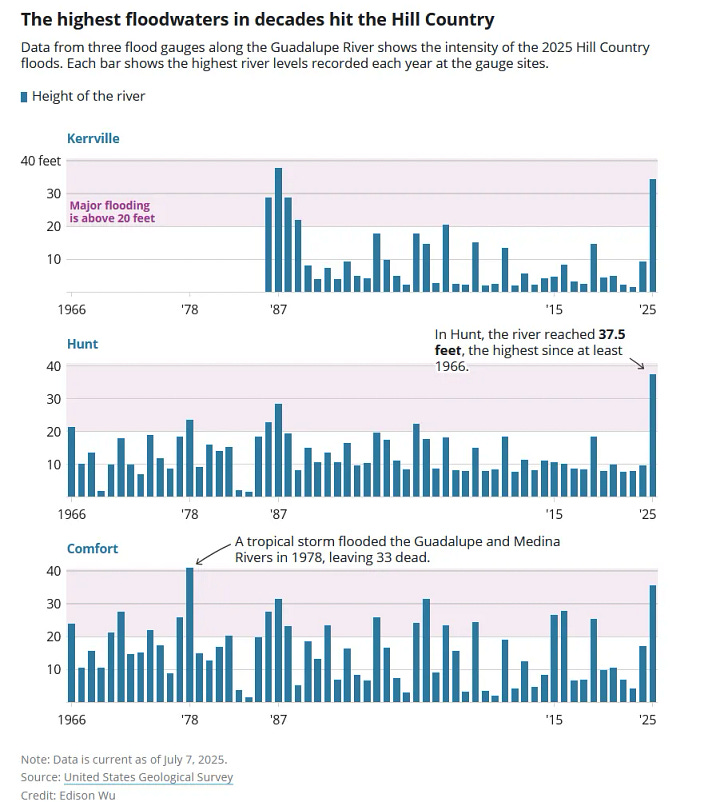

In 1987, there was flash flooding along the Guadalupe river (the river rose 29 feet) that led to the drowning of 10 teenagers, who were at a summer camp along the river, during a botched evacuation from the flood waters. The crest in 1987 was higher than the one in 1978…

There is a pattern here.

Even one that Kerr County Commissioner, Tom Moser, noted in 2016, as reported by the Texas Tribune, that Kerr county was in, “…one of the highest flood-prone regions in the entire state where a lot of people are involved,” and other communities were investing in robust, modern emergency flood warning systems, that in the aftermath of the July 4th flooding would be credited with saving all lives in the community.

The Kerr community that has grown—the population has increased more than 9% since 2020 and as a local meteorologist, Doug Burgess, commented on all the construction along the Guadalupe river:

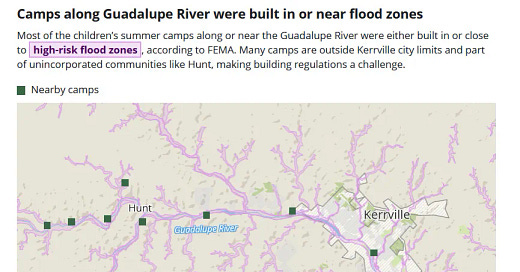

‘They’ve been building up and building up and building up and doing more and more projects along the river that were getting dangerous,” Burgess recalls. “And people are building on this river, my gosh, they don't even know what this river's capable of.”—Texas Tribue

This reckless expansion raises critical questions about responsibility and the forces driving such widespread vulnerability.

Who allowed this unchecked development? Public officials across Texas, through their zoning and permitting decisions.

Who approved the plans for construction in these dangerous areas? Engineers, whose professional duty includes safeguarding public welfare.

And who ultimately profited from these risky drawings and construction? Contractors.

The answers reveal a systemic failure where profit and political expediency frequently trump safety. This isn't an isolated incident; Texas, in particular, has a deeply entrenched history of ignoring and delaying payment for preventative solutions to lessen the harm from intense acts of nature, particularly related to flooding.

“When compared to other states, Texas has recorded the most flood-related deaths. Over the last decade, the number of deaths in Texas was almost twice as high as the second highest state, North Carolina.”-Texas Tribune

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey hit Houston and the resulting flooding led to nearly 100 deaths and damages over $150 billion dollars. NPR and PBS reported, last month, that while Harvey left neighborhoods under 4-6 ft of water, the city has implemented a design that may reduce flooding by only by one foot.

This minimal mitigation, a mere gesture against the tide of likely future devastation, exposes a dangerous fallacy. There is a prevalent misconception, fueled by a torrent of political rhetoric, that the public is somehow "better off" because of the gutting of government regulation and oversight. This narrative paints regulation as a burdensome monster, an overreaching, job-killing force that stifles innovation and individual liberty.

But the "regulatory monster" is, in fact, a monster only in the sense that it is not real. It is a phantom, a rhetorical construct designed to distract from the very real and devastating consequences of its absence.

Where are the true 'monsters'?

They are found in the unchecked development of floodplains, in the silent consent given to engineers who fail to hold paramount the safety of the public when approving plans, in the political will that consistently prioritizes short-term economic gain over long-term community resilience.

When the public believes the government is stifling freedom and cannot assess risk, you create the conditions for preventable fiascos.

The convenient fiction of a burdensome government allows for the systematic dismantling of the very mechanisms that could protect them, leaving communities vulnerable to preventable disasters.

The true monster, then, is not regulation, but the ideological blindness that refuses to acknowledge the critical role of collective action, sound engineering principles, and genuinely enforced standards in safeguarding lives and livelihoods.

We saw it—the deaths, damages, and systemic failures resulting from ideological blindness and the gutting of regulations— in North Carolina last fall. We saw it in Texas at the beginning of the month. And we are guaranteed to see it again, unless we finally demand accountability from those who swear to protect us.

You made it to the end. Here is your prize. Humans like puzzles.

If only we could get this read out on Fox.

With regard to math (my favorite subject) here is a paper on geometric algebra (another favorite subject ) titled, "Imaginary Numbers are not Real"

https://worrydream.com/refs/Gull_1993_-_Imaginary_Numbers_are_not_Real.pdf

My favorite mathematician is Emmy Noether. If she had lived a few more years she would have won the Nobel Prize in physics for Noether's theorem -

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmy_Noether

All math students should know about her.